PCOS is a very common condition, affecting at least one out of every ten women worldwide.

The name “PCOS” was coined by two doctors, Irving Stein and Michael Leventhal, in 1935. They examined a number of women, who complained about irregular menstrual bleeds, difficulties to get pregnant and increased body hair growth. Polycystic ovaries describe ovaries that have multiple small cysts. These cysts are follicles that have not developed properly enough to release an egg due to hormonal abnormalities.

The term “PCOS” is widely used but misleading, as it seems to suggest that PCOS is a condition caused by something being wrong with the ovaries. However, in fact, women with PCOS have changes in their hormones including excess insulin (insulin resistance) and male hormones (androgens) affecting the ovaries and not the other way round.

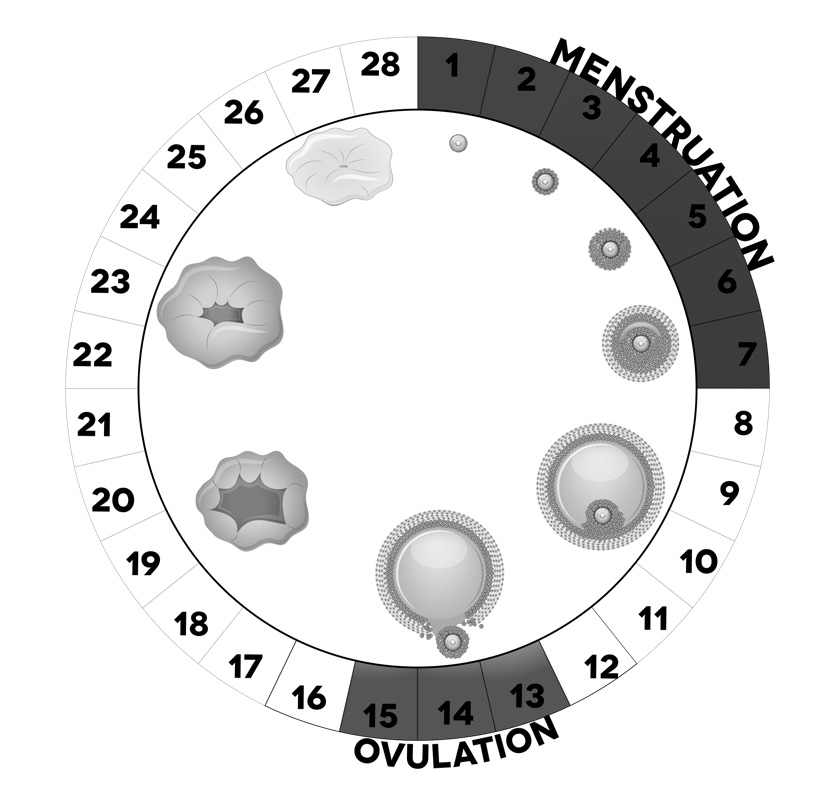

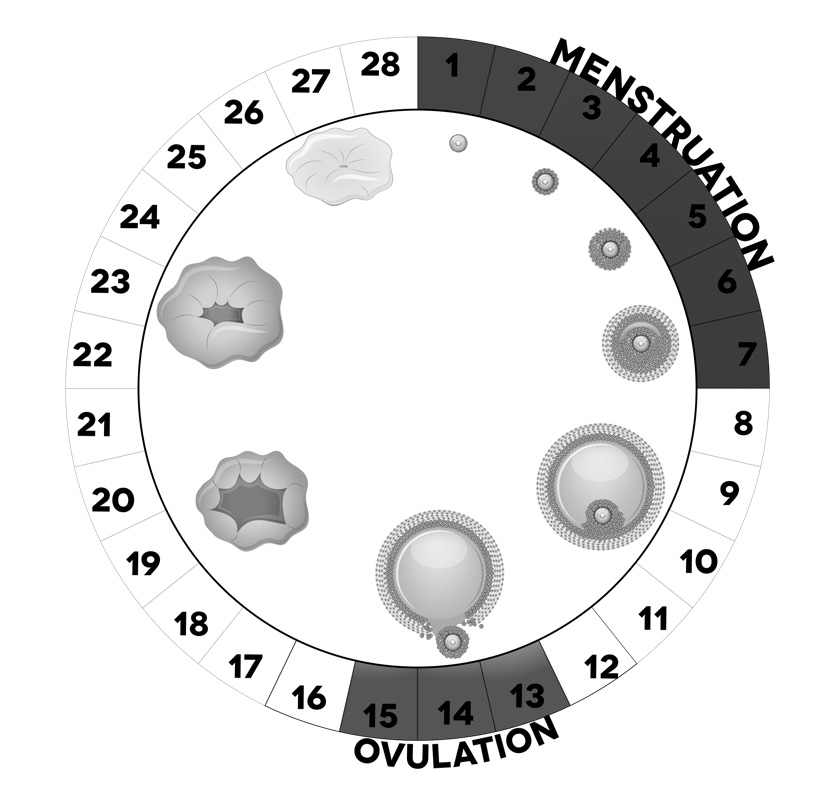

Every girl is born with millions of tiny follicles in her ovaries. Follicles are fluid-filled sacs, in which eggs can develop during the fertile years of a woman’s life. Each month one (or sometimes two) follicle releases an egg. The egg, when fertilised with sperm, can result in pregnancy. This monthly release of an egg from the ovaries is called “ovulation”.

After ovulation, the follicle cells produce a hormone called progesterone that prepares the inner lining of the womb for pregnancy. However, if the egg is not fertilised, progesterone levels drop and the inner lining of the womb is shed, causing the menstrual bleed or “Menstruation”.

Women with PCOS usually have increased levels of male hormones (“androgens”) in their blood, though at much lower levels than in men. Too much male hormone (“androgen excess”) can cause problems with the skin, including oily skin and acne, increased growth of dark and coarse hair on their body, termed “hirsutism”, or also loss of scalp hair (“alopecia”).

Male hormones are also important for the early stages of egg development. In PCOS, male hormone levels are increased, which drives more ovarian follicles to develop towards the egg release stage. However, too much male hormone blocks the later stages of egg development. In women with PCOS, the ovaries only release an egg irregularly or not at all, which is called “Anovulation”.

If the doctor examines the ovaries of a woman with PCOS using ultrasound, it often looks as if there are lots of small “cysts” in the ovaries. However, they are in fact immature follicles, leading to the appearance of “polycystic ovaries” on the ultrasound scan.

How is PCOS diagnosed?

A diagnosis of PCOS can be made when you have any two of the following:

- Irregular, infrequent or absent periods.

- Excess facial and/or body hair and/or blood tests revealing excess levels of male hormones (androgens).

- A transvaginal ultrasound revealing at least 20 follicles measuring 2–9 millimetres in diameter and/or an overall increased ovarian volume (greater than 10 millilitres).

The symptoms of PCOS are highly variable from woman to woman. Before a diagnosis of PCOS is made, the doctor will also usually

exclude other conditions that could cause similar signs and symptoms, which includes conditions that affect the function of hormone-producing glands (ovaries, adrenals, thyroid and pituitary glands). This is usually done by a combination of clinical examination and blood tests.

What are the consequences of PCOS?

PCOS affects the function of the ovaries, as described above, leading to

irregular periods. In addition, if there are few or no period bleeds, the inner lining of the womb is not regularly shed, which can cause an increased risk of womb cancer (endometrial cancer) in the future. It is therefore recommended that women with PCOS should have a period bleed at least every three months and that if this does not happen spontaneously, medication can be given.

Irregular bleeds indicate irregular or absent egg release. This can cause

problems with getting pregnant. This can be best addressed by an endocrinologist (=hormone specialist doctor) and a gynaecologist (women’s health specialist doctor).

The increased male hormone levels in PCOS can affect the skin, causing acne, increased facial and/or body hair growth and, in some women, hair loss on the scalp. These problems are best addressed by an endocrinologist (hormone specialist doctor) in consultation with a dermatologist (skin specialist doctor).

In many women, PCOS is associated with weight gain and difficulty losing weight, which can make other PCOS symptoms worse. This can cause insulin resistance, when the body no longer responds to normal levels of the sugar-regulating hormone insulin. This leads to an increase in insulin levels, which in turn increase male hormone levels. However, some women with PCOS have normal body weight (“Lean PCOS”) but still struggle with fertility and excess body hair driven by excess male hormones.

In women with overweight or obesity, weight loss usually improves symptoms of PCOS, as weight loss lowers both insulin and male hormone levels. This can be best addressed by a team that has the skills necessary for weight and diabetes management including a specialist endocrinologist (hormone specialist doctor), an expert dietitian who can give advice on diets and nutrition, and, occasionally, a psychologist.

Women with PCOS have been shown to be at an increased risk of Type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, excess fat in the liver, obstructive sleep apnoea ( a condition of repeated episodes of holding breath during sleep), and possibly also heart disease. Metabolic risk increases with body weight but also with the severity of androgen excess.

PCOS is now considered a lifelong metabolic disorder rather than a condition that only affects women of reproductive age.

Women with PCOS also often report feeling low in energy, feeling anxious and depressed, and having an impaired body image. Counselling and other psychological therapies can help with these symptoms.

What is the cause of PCOS?

PCOS often runs in families, which means that the daughter of a woman with PCOS has a higher risk to develop PCOS herself. However, examining the genetic information of women with PCOS in several large studies has not identified a specific “PCOS gene” that one could test for. Many women with PCOS are resistant to the action of the sugar- regulating hormone insulin in their body (“insulin resistance”), producing higher levels of insulin to overcome this. Insulin resistance is also driven by obesity, but also regularly found in women with PCOS, who have normal body weight.

Insulin resistance has been shown to increase male hormone levels and androgen excess increases insulin resistance. It appears that androgen excess and insulin resistance are linked in a “vicious circle” for people with PCOS. Both insulin resistance and increased male hormone levels can increase the risk of developing Type 2 diabetes.

Research currently examines how androgen excess and insulin resistance are linked. Initial evidence suggests that having one increases the likelihood of having the other, and that treating either one can help to treat the other. Understanding more about how androgens and insulin are linked in PCOS will hopefully help to identify the women with PCOS who are at highest risk of developing metabolic complications. We also hope that this research will help to develop new therapies for the treatment of PCOS and prevention of its complications.

Please ask us about our ongoing research into PCOS. Women with PCOS and their children have the opportunity to participate in a number of research studies carried out here in Birmingham.

PCOS is not all doom and gloom!

We now know that

PCOS is a lifelong metabolic disorder and that women with PCOS need attention by their GP throughout life and not only during the reproductive years. Establishing care concepts for women with PCOS will highly likely reduce their disease burden and also prevent the development of metabolic complications. PCOS affects women of all ethnic backgrounds and while the frequency of PCOS has not been examined in all countries, it is increasingly clear that

women of South Asian or African background may be at a higher risk of PCOS. This is similar to the well-known higher risk of Type 2 diabetes in people with South Asian ethnic background. This is thought to be due to the fact that people in these regions had to deal with shortage of food over many centuries, which led to the selection of individuals who can survive with very little food. PCOS affects women of all ethnic backgrounds and while the frequency of PCOS has not been examined in all countries, it is increasingly clear that women of South Asian or African background may be at a higher risk of PCOS. This is similar to the well-known higher risk of Type 2 diabetes in people with South Asian ethnic background. This is thought to be due to the fact that people in these regions had to deal with shortage of food over many centuries, which led to the selection of individuals who can survive with very little food.

PCOS affects women of all ethnic backgrounds and while the frequency of PCOS has not been examined in all countries, it is increasingly clear that women of South Asian or African background may be at a higher risk of PCOS. This is similar to the well-known higher risk of Type 2 diabetes in people with South Asian ethnic background. This is thought to be due to the fact that people in these regions had to deal with shortage of food over many centuries, which led to the selection of individuals who can survive with very little food.

The name “PCOS” was coined by two doctors, Irving Stein and Michael Leventhal, in 1935. They examined a number of women, who complained about irregular menstrual bleeds, difficulties to get pregnant and increased body hair growth. Polycystic ovaries describe ovaries that have multiple small cysts. These cysts are follicles that have not developed properly enough to release an egg due to hormonal abnormalities.

The term “PCOS” is widely used but misleading, as it seems to suggest that PCOS is a condition caused by something being wrong with the ovaries. However, in fact, women with PCOS have changes in their hormones including excess insulin (insulin resistance) and male hormones (androgens) affecting the ovaries and not the other way round.

Every girl is born with millions of tiny follicles in her ovaries. Follicles are fluid-filled sacs, in which eggs can develop during the fertile years of a woman’s life. Each month one (or sometimes two) follicle releases an egg. The egg, when fertilised with sperm, can result in pregnancy. This monthly release of an egg from the ovaries is called “ovulation”.

After ovulation, the follicle cells produce a hormone called progesterone that prepares the inner lining of the womb for pregnancy. However, if the egg is not fertilised, progesterone levels drop and the inner lining of the womb is shed, causing the menstrual bleed or “Menstruation”.

The name “PCOS” was coined by two doctors, Irving Stein and Michael Leventhal, in 1935. They examined a number of women, who complained about irregular menstrual bleeds, difficulties to get pregnant and increased body hair growth. Polycystic ovaries describe ovaries that have multiple small cysts. These cysts are follicles that have not developed properly enough to release an egg due to hormonal abnormalities.

The term “PCOS” is widely used but misleading, as it seems to suggest that PCOS is a condition caused by something being wrong with the ovaries. However, in fact, women with PCOS have changes in their hormones including excess insulin (insulin resistance) and male hormones (androgens) affecting the ovaries and not the other way round.

Every girl is born with millions of tiny follicles in her ovaries. Follicles are fluid-filled sacs, in which eggs can develop during the fertile years of a woman’s life. Each month one (or sometimes two) follicle releases an egg. The egg, when fertilised with sperm, can result in pregnancy. This monthly release of an egg from the ovaries is called “ovulation”.

After ovulation, the follicle cells produce a hormone called progesterone that prepares the inner lining of the womb for pregnancy. However, if the egg is not fertilised, progesterone levels drop and the inner lining of the womb is shed, causing the menstrual bleed or “Menstruation”.

Women with PCOS usually have increased levels of male hormones (“androgens”) in their blood, though at much lower levels than in men. Too much male hormone (“androgen excess”) can cause problems with the skin, including oily skin and acne, increased growth of dark and coarse hair on their body, termed “hirsutism”, or also loss of scalp hair (“alopecia”).

Male hormones are also important for the early stages of egg development. In PCOS, male hormone levels are increased, which drives more ovarian follicles to develop towards the egg release stage. However, too much male hormone blocks the later stages of egg development. In women with PCOS, the ovaries only release an egg irregularly or not at all, which is called “Anovulation”.

If the doctor examines the ovaries of a woman with PCOS using ultrasound, it often looks as if there are lots of small “cysts” in the ovaries. However, they are in fact immature follicles, leading to the appearance of “polycystic ovaries” on the ultrasound scan.

Women with PCOS usually have increased levels of male hormones (“androgens”) in their blood, though at much lower levels than in men. Too much male hormone (“androgen excess”) can cause problems with the skin, including oily skin and acne, increased growth of dark and coarse hair on their body, termed “hirsutism”, or also loss of scalp hair (“alopecia”).

Male hormones are also important for the early stages of egg development. In PCOS, male hormone levels are increased, which drives more ovarian follicles to develop towards the egg release stage. However, too much male hormone blocks the later stages of egg development. In women with PCOS, the ovaries only release an egg irregularly or not at all, which is called “Anovulation”.

If the doctor examines the ovaries of a woman with PCOS using ultrasound, it often looks as if there are lots of small “cysts” in the ovaries. However, they are in fact immature follicles, leading to the appearance of “polycystic ovaries” on the ultrasound scan.

Women with PCOS also often report feeling low in energy, feeling anxious and depressed, and having an impaired body image. Counselling and other psychological therapies can help with these symptoms.

Women with PCOS also often report feeling low in energy, feeling anxious and depressed, and having an impaired body image. Counselling and other psychological therapies can help with these symptoms.